This month we are beginning a three part series on extraction complications. These three newsletters will cover the most common complications, why they happen, where they happen, how to avoid them and how to deal with them. Rest assured that I have personally experienced almost every problem covered in this series.

PART ONE:

The most common extraction complications and why they happen

Dental extractions may be the most commonly indicated surgical procedure in veterinary medicine. Historically, the only reason to extract teeth was because they had excessive mobility. Anyone can extract a mobile tooth because they are sitting in a mushy area of demineralized soft bone. Mobile teeth are very forgiving of procedural errors. In reality, most teeth that should be extracted in small animal patients are not mobile. Using techniques more appropriate for mobile teeth results in a variety of different complications, which are easier to prevent than treat.

The common complications

INCOMPLETE EXTRACTION

When an owner gives consent for you to extract a tooth, that implies “the entire tooth”. Leaving fragments of teeth in place is not appropriate, may cause legal problems for the operator, may result in client dissatisfaction, may result in draining tracts, nasal discharge, unrecognized pain and damage to adjacent teeth. The technique of using crown amputation and intentional root retention as the routine “extraction technique” in feline patients frequently results in retained roots and draining tracts. The roots do not magically disappear. For a more detailed description of when this technique may be appropriately employed, see January 2011 newsletter on feline tooth resorption.

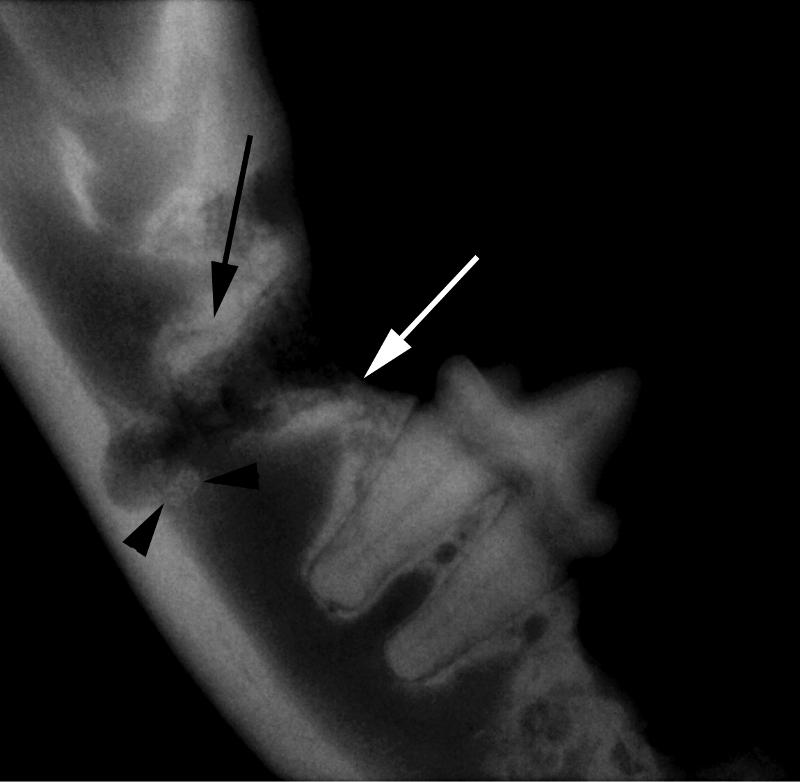

Figure 1. Radiograph after an attempt to extract a right lower molar in a feline patient using the crown amputation technique. Root fragments are still present on the mesial and distal aspects of the alveolus (arrows) and a root fragment has been displaced into the mandibular canal (arrowheads). The inferior alveolar nerve in the mandibular canal has likely been damaged. “Drilling out roots” commonly causes these problems.

ROOT FRACTURE

Fractured roots are commonly encountered when extracting teeth. There are a number of different reasons why this can occur, including overzealous extraction technique, using dental elevators in a levering (rather than a rotary) fashion, pre-existing damage to the root structures (common in feline tooth resorption), or challenging dental anatomy. Most roots are not circular in cross-section and many have longitudinal developmental grooves. Roots are usually not round structures in a round socket. Many roots are curved, hooked, or bulbous near the apex. These anatomic variations can make it impossible to “pry” the root out of solid alveolar bone. It is surprising that more roots do not fracture during extraction.

ROOT DISPLACEMENT

In certain anatomic areas, there is a possibility of pushing a root into a location where it might cause clinical signs or be difficult to retrieve. The most common examples would be root displacement into the nasal passages, maxillary recess (located palatal to the upper fourth premolars in dogs), mandibular canal or retrobulbar space.

HEMORRHAGE

When a major artery is damaged, the amount of bleeding can be disconcerting. This can occur with any extraction site, but is most common when working near the inferior alveolar (mandibular) artery located in the mandibular canal or the infraorbital artery located in the infraorbital canal (above the upper fourth premolar and molars) in both dogs and cats. Damage to the major palatine artery and middle mental artery may also result in significant bleeding.

IATROGENIC DAMAGE TO ADJACENT ANATOMIC STRUCTURES

There are a number of ways that iatrogenic damage occurs during dental extractions. Adjacent teeth may be damaged with high-speed drills, exposing dentin or the root canal system. Sharp dental elevators or periosteal elevators can slip off their intended location and lacerate adjacent structures such as the orbit and neurovascular bundles. Oro-nasal fistulas may occur secondary to instrument displacement into the nasal passages. The mandible can easily fracture when extracting teeth, especially the large mandibular canine teeth and first molars that make up a large percentage of the cross-sectional diameter of the mandible.

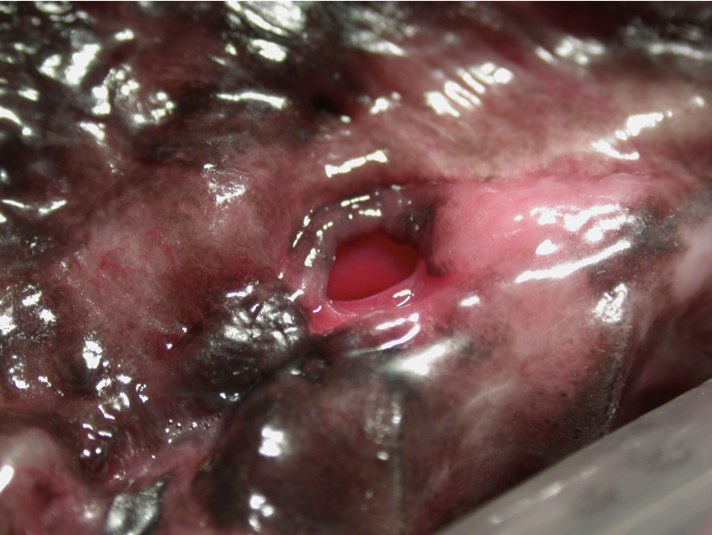

Figure 2. An oro-nasal fistula secondary to a dental elevator being displaced into the nasal passages. The displacement was recognized, but the closure was inappropriate for the situation, resulting in the fistula.

LEAVING UNRECOGNIZED PATHOLOGIC TEETH IN PLACE

Very commonly, teeth are extracted without recognizing that pathology has already extended to adjacent teeth. Endodontic disease may extend from the root apex of one tooth to the apex of a root in an adjacent tooth. This is commonly seen in maxillary molars and upper fourth premolars in dogs. The radiographic pathology may be readily apparent in only one of the effected teeth, but adjacent teeth may require treatment.

DEHISCENCE

The author recommends that all extraction sites, regardless of the degree of existing pathology, be sutured closed. There is no such thing as an extraction site that “needs to drain”. Faster healing and improved patient comfort are just two advantages of closing all extraction sites. When flaps dehisce, delayed healing results.

Why Do Complications Occur?

INADEQUATE VISUALIZATION

Not being able to see what you are doing certainly complicates the procedure. Good lighting and magnification will both substantially improve the quality of your oral surgery and help prevent errors. Feline dentistry is very difficult without magnification. Despite good near vision and many years of experience, the author cannot do an acceptable job in feline patients without magnification. Many practitioners would benefit from being more aggressive with flap creation and surgical exposure. As one well known Ontario practitioner said, “I think we are wimpy flappers”.

Figure 4. Adequate exposure allows visualization of the middle mental neurovascular bundle (arrow) and facilitates removal of buccal bone.

Figure 5. Some type of magnification will greatly improve the quality of your oral surgery. From left to right are pictured an Optivisor headband, semi-custom loupes (Miltex) and fully customized surgical telescopes (Designs for Vision).

IMPROPER EQUIPMENT

As in most types of surgery, having the right equipment makes all the difference. High-speed delivery equipment with an integrated water spray is an absolute must. Micromotor handpieces with adjustable speed and no integrated water spray are a poor substitute for a high speed drill, make the procedure much harder and burn bone. An adequate assortment of burs, a selection of several types of the thin luxator-type dental elevators, good general surgical instruments suited for the oral cavity, sharp periosteal elevators, alveolar curettes, root tip picks, appropriate suture material and some miscellaneous items will make your life much easier.

Figure 6. The electric micromotor pictured above in this typical scaler/micromotor combination unit makes an excellent polishing unit, but is woefully inadequate for any type of oral surgery, including extractions. Unfortunately, they are sold with a variety of adapters that allow you to attach burs onto the unit.

IMPROPER TECHNIQUE

There are a few common technique errors that contribute to most of the complication extractions seen in veterinary dentistry. Trying to extract a solid tooth without using a “surgical extraction” technique is probably the most common reason for error. When teeth are not mobile, they cannot be extracted easily without first raising a mucoperiosteal flap and drilling away a portion of the buccal (lateral) bone overlying the root. A 2-3 mm deep “gutter” is then created on either side of the root to allow straight line placement of a dental luxator into the PDL space. Proper preparation allowing an instrument to be placed into the PDL space is the single most helpful thing for extraction of solid teeth. (Compare and contrast this with trying to lever a tooth out of mushy bone, which is all that is required for extraction of mobile teeth. The techniques are totally different.)

A thin and sharp luxator-type dental elevator that matches the curvature of the root is then wiggled and pushed into the periodontal ligament (PDL) space, where it can exert mechanical leverage between the root and the alveolar bone. While holding the instrument in the PDL space, the instrument is twisted to open a space between the tooth and bone and is held in place for 30 seconds, fatiguing the PDL and allow hemorrhage to fill into the widened PDL space. Patience is a virtue during this phase. The instrument is gradually advanced deeper into the ligament space and the same technique is applied around the circumference of the tooth as needed.

After the root is luxated out of the alveolus, the flap is lengthened to eliminate any tension and sutured into place with sutures placed 2-3 mm apart. While some veterinary dentists use a simple continuous suture pattern, the author prefers simple-interrupted sutures for better security. One other point to remember is that after the surgery is completed, all teeth should still have a “collar” of attached gingiva completely around them.

The aforementioned steps are what are generally acknowledged to constitute a “surgical extraction”. Utilizing this technique facilitates extraction of teeth with solid roots.

UNRECOGNIZED ANATOMY/PATHOLOGY

Dental radiographs are required for assessment of existing pathology and appropriate treatment planning. Unless you take dental radiographs, it is not possible to treat the patient correctly. Correlation of clinical exam and radiographic findings will help prevent complications.

Some problems are associated with specific types of breeds. For example, many brachycephalic breeds have rotated third premolars that are crowded tightly against the fourth premolars, trapping debris and predisposing to periodontal disease and bone loss in that area. These third premolar teeth commonly require extraction to save the important fourth premolar, a major chewing tooth. In some cases, the roots of the third premolars are separated from the nasal passages by only a thin layer of nasal mucosa, making it very easy to displace the root into the nose. This particular area is also a common area to encounter excessive hemorrhage, making visualization more difficult.

Next month: Where do complications usually occur and how can you avoid them?