Where do extraction complications occur and how can you avoid them?

This month we continue the three part series on veterinary dental extraction complications. Part 1 of Extraction Complications is available here, Part 3 will be posted in early August.

WHERE DO COMPLICATIONS MOST COMMONLY OCCUR?

MAXILLARY PM4/M1/M2

The infraorbital canal and the associated infraorbital neurovascular bundle are located just above these teeth. The large vessels in the canal can be lacerated, the nerves (sensory to the teeth and upper lip) can be damaged or a root may be displaced into the infraorbital canal.  The palatal root of the fourth premolar can be displaced into the maxillary recess, which is connected to the nasal passages. This would have the same effect as displacing the root into the nasal passages. If a sharp elevator slips off the last molar, the orbit and all of the structures in the retrobulbar space may be traumatized. The anatomic structures in this area include the optic nerve, autonomic innervation to the eye, the maxillary artery and the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve.

The palatal root of the fourth premolar can be displaced into the maxillary recess, which is connected to the nasal passages. This would have the same effect as displacing the root into the nasal passages. If a sharp elevator slips off the last molar, the orbit and all of the structures in the retrobulbar space may be traumatized. The anatomic structures in this area include the optic nerve, autonomic innervation to the eye, the maxillary artery and the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve.

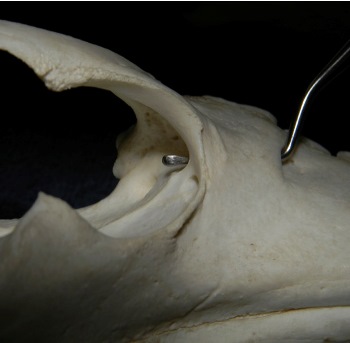

Figure 1. Dorsal view of the maxilla, showing the infraorbital canal running just dorsal to the upper fourth premolar and molars. The caudal foramen is located directly below the globe.

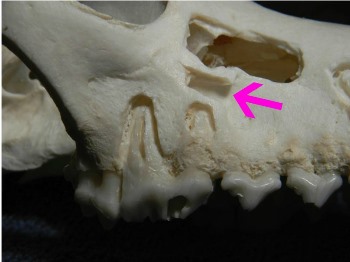

Figure 2. Right maxilla, showing the roots of the upper fourth premolar (#108) located just ventral to the infraorbital canal (arrow).

Figure 3. Same specimen as above, showing the nasal passages and maxillary recess lying medial to the palatal root of the upper fourth premolar. The infraorbital canal is indicated by the arrow.

Figure 4. A sharp dental instrument can easily slip off the distal molars (#209 and #210) and damage the globe or other orbital structures.

MANDIBULAR CANINES

These teeth make up the majority of the mandibular cross-sectional area. There is actually more tooth than bone in the area of the mandibular canines. If excessive force is used to extract a solid lower canine tooth, severe separation of the mandibular symphysis or mandibular fracture may result. Additionally, the middle mental foramina and the associated neurovascular bundles are located on lateral surface of the mandible near the apex of the roots of the lower canine teeth. Damage to the bundle may cause significant hemorrhage or permanent loss of sensation of the lower lip.

MAXILLARY CANINES

The roots of the maxillary canines are frequently separated from the nasal passages by a thin layer of bone or membranous material. Extraction can easily result in communication between the extraction site and nasal passages. If this is not recognized and addressed during closure, an oro-nasal fistula may result. The infraorbital neurovascular bundle exits the maxilla above the distal root of the upper third premolar and courses rostrally in the lip over the mid-root area of the maxillary canines. Take care to avoid these structures when making incisions and raising extraction flaps.

Figure 6. Dental radiograph of the left maxilla, showing an incisor displaced into the nasal passages during extraction.

Figure 7. A dorsal view of the same patient as in figure 6. Utilizing both views will help localize the location of the tooth for treatment planning.

LOWER M1

The mandibular molars make up a large percentage of the mandible, especially in smaller dogs in which the roots of these teeth commonly extend completely to the ventral cortex of the mandible. The roots of these teeth may be located lateral to, within, or in some cases medial to the mandibular canal containing the inferior alveolar (mandibular) neurovascular bundle. Iatrogenic damage to these structures should be avoided. In some cases, large amounts of bone removal are required to extract these teeth, risking fracture. In many cases, the roots of these teeth exhibit anatomical variations, such as curved roots, roots that extend down to (or even into) the ventral cortex, hooks in the ends of the roots and grooves in the roots with bone grown into them. All of these can affect the amount of bone removal required to extract the tooth.

ALL TEETH ADJACENT TO MN CANAL

All of the mandibular premolars and molars lie in close association with the mandibular canal and it’s neurovascular bundle.

Figure 8. Right mandible showing the close association of the premolars and first molar (#409) with the mandibular canal and the neurovascular bundle contained therein.

ALL TEETH ADJACENT TO NASAL PASSAGES

The maxillary incisors and premolars all lie in close association with the nasal passages and damage to the turbinates, excessive hemorrhage and displacement of the roots into the nasal cavity during extraction are all possible.

TEETH WITH TOOTH RESORPTION, ESPECIALLY CATS

Classic Tooth Resorption (TR), occurring at or near the gingival margin and formerly known as resorptive lesions, neck lesions, feline cavities, etc. are commonly seen in feline patients and are occasionally seen in canine patients. The areas of resorption weaken the teeth near the gingival margin, and many teeth in feline patients actually have bulbous roots locked in solid bone. The combination of the weakened tooth structure and bulbous roots makes extraction using just elevators very difficult, if not impossible. A very misused technique in veterinary medicine is “extraction” of teeth in feline patients by simply amputating the crown and drilling out some of the root, hoping that the remaining root structure will somehow be magically resorbed. In many cases, the roots do not resorb, instead remaining as painful sequestrae for many years. These patients are in pain, but rarely exhibit any behaviors that would alert the owner to their discomfort.

HOW TO AVOID EXTRACTION COMPLICATIONS

Like many general surgical complications, complications of dental extraction are more easily avoided than they are treated. Following are some tips that may help prevent future problems.

DENTAL RADIOGRAPHS

Simply put, dental radiographs are an absolute requirement for extractions. Regardless of what you think about a potential extraction, dental radiographs frequently prove you wrong. Anatomic variation, developmental variation, missing roots, extra roots, hooked roots, grooved roots, impending pathologic fractures, loose teeth that turn out to be neoplasia, and the list goes on. You cannot do quality work in dentistry without taking a lot of dental radiographs. Post-extraction dental radiographs are advised to document the procedure and verify that the entire root has been extracted.

ADEQUATE LIGHTING AND MAGNIFICATION

Dental surgery is microsurgery. If you can see what you are doing, your job is much easier. Making extractions easy requires that you see small structures such as the periodontal ligament space. I believe that even a person with good near vision cannot do a good job in feline dentistry without some type of magnification. If you want to double the quality of your work, consider purchasing surgical telescopes custom made for you. This is why almost all human dentists have them. Bright lighting constricts the pupils, improving your the focal depth of field, similar to a higher f-stop number on a camera. The light is best used in a direction parallel to the direction you are looking.

ADEQUATE EXPOSURE

Raising mucoperiosteal gingival flaps provides the exposure needed for removal of the buccal (lateral) bone covering the roots. Since most teeth requiring extraction have their roots in solid bone, the operator needs to create space for them to be luxated out of the alveolus, which the lateral bone removal accomplishes. Failure to aggressively raise the flap enough to allow lateral bone removal is a common reason for complications. In most cases, one or two vertical incisions are made and the flap is somewhat rectangular in shape. When making two vertical incisions for a flap, make sure they diverge as they go away from the gum line, making the base of the flap wider. When making a single vertical incision, angle the incision slightly away from the tooth to be extracted. The goal is to have the base of the flap be wider than the gingival marginal edge of the flap, which helps eliminate tension when the flap is eventually sutured into place.

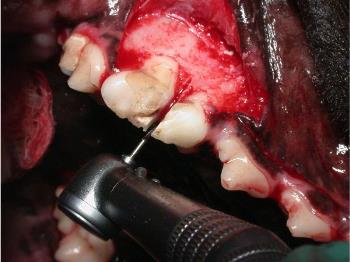

Figure 9. Appropriate exposure for sectioning and extraction of the right upper fourth premolar (#108).

CORRECT EQUIPMENT

As mentioned above, dental extractions require the use of a high-speed drill with an integrated water spray. A low speed electric micro-motor turning at 1/10th the speed, with no integrated water spray, is a poor substitute and takes much longer. A list of suggested equipment and materials that will make your life simpler is included at the end of the final part of this series next month.

Next Month: How to deal with common complications