Base narrow mandibular premolar teeth (BNMCT) are commonly seen in small animal practice. When left untreated, various types of pathology can develop secondary to the traumatic occlusion of the lower canine teeth with the maxillary dentition and palatal soft tissues. In some cases, what starts as a mild traumatic occlusion can worsen over time. This case illustrates what can happen when minor trauma secondary BNMCT remains untreated for an extended period of time.

A 6 year old NM German shepherd presented at Animal Dental Care for evaluation of his occlusion. He had recently shown some reluctance to chew hard food and treats, and had lost some weight. The owner also noted that he had been acting “older” recently. His malocclusion had been previously noted, but it did not seem to be causing any problems.

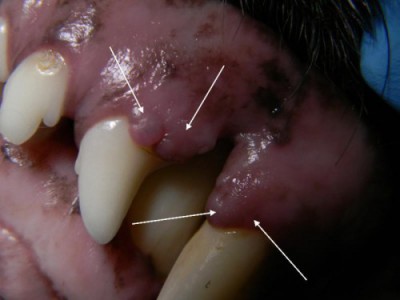

Oral exam showed that his left lower canine tooth (304) was tipped palatally, protruding into the gingival and palatal tissues between the left maxillary third incisor (203) and canine tooth (204) (Fig. 1). A draining tract was noted in the diastema in this same area (Fig. 2, 3 and 4). Some gingival hyperplasia was also evident around 203 and 204, which increased the amount of traumatic contact. The left upper third incisor (203) also had an area of root exposure with dentin in this area exposed to the oral cavity.

Figure 1. The left lower canine (304) is protruding into the palatal tissues. Gingival hyperplasia (arrows) can be seen around the left upper third incisor and canine teeth. A small enamel defect with dentin exposure is visible near the gingival margin of the second incisor (202).

Figure 2. A periodontal probe is placed next to the periodontal abscess.

Figure 3. The periodontal probe has been placed into the draining tract, showing the extent of the lesion.

Figure 4. The defect (circle) can be see in the palatal soft tissues. Additionally, an area of dentin exposure (arrow) is visible in the root of the third incisor. This was created by traumatic contact of the lower canine tooth.

The patient was very reluctant to allow an oral exam. The owner was advised that an anesthetized exam and dental radiographs would be required to evaluate potential pathology and guide treatment options.

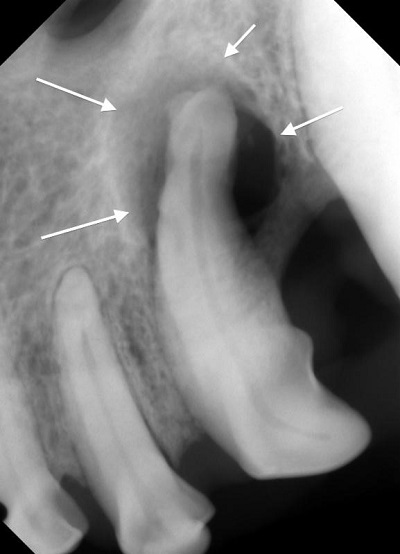

Under anesthesia, the patient’s teeth were scaled and polished and a complete oral exam was performed. Dental radiographs (Fig. 5) showed that 203 was non-vital with a large area of periapical bone loss.

Figure 5. Dental radiograph of the left upper third incisor, showing a large periapical lucency (arrows) and radiographic evidence of root resorption in the apical half of the root.

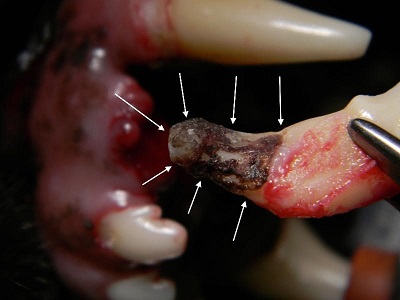

The third incisor was extracted and the site was cleaned, irrigated, and partially closed with absorbable suture material (Fig 6 and 7). The entire apex of this tooth had undergone resorption and was covered in calculus (Fig 8).

Figure 6. After extraction of 203 and partial closure of the site. An area of gingival hyperplasia on the canine tooth has been reduced and re-contoured utilizing an electrosurgical unit.

Figure 7. palatal view after treatment.

Figure 8. Tooth 203 after extraction, showing the the area of root resorption and calculus deposition on the root.

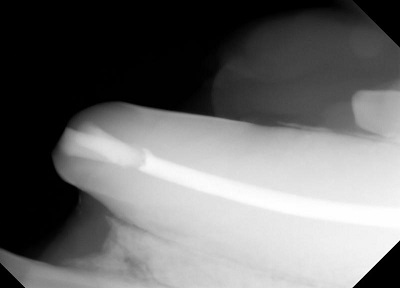

The crown height of the left lower canine tooth (304) was shortened to eliminate the traumatic contact with the maxillary soft tissues, and was treated with root canal therapy (Fig 9). A small area of missing enamel near the gingival margin on the facial aspect of the left upper second incisor was smoothed and sealed with bonded resin. Areas of gingival hyperplasia were present on all four canine teeth. These areas were reduced to normal height and contour. Patient recovery and healing were both uneventful.

Figure 9. Final radiograph after crown reduction and root canal therapy of the left lower canine tooth (304). The composite restorations, intermediate restorative layer and root obturation material are all visible.

The large bony defect in this patient likely started as mildly traumatic lesion, with the lower canine protruding into the palatal soft tissues 3-4 mm. Over time, the defect became ulcerated, with food and debris eventually packing into the site. The initially shallow defect then extended into deeper tissues, eventually creating a periodontal abscess with a draining tract visible in the diastema. The endodontic infection of the left upper third incisor (203) was possibly secondary to dentin exposure created by traumatic contact of the lower canine tooth. Bacterial migration through the exposed dentin tubules resulted in endodontic infection with a large periapical lesion. The endodontic infection eventually caused apical resorption and apical calculus deposition.

Six months after treatment, the owner noted that the patient was acting much happier and was eating hard food and treats enthusiastically. Based on the pictures and radiographs, I think we can all agree this was an uncomfortable lesion. Yet the patient never showed obvious clinical signs that alerted the owner to the presence of an oral/dental problem. Fortunately, the referring veterinarian noted the periodontal abscess and advised the owner to seek additional care. Dental radiographs showed pathology far beyond the initially observed draining tract and were critical in guiding correct treatment in this patient.

Patients with mild trauma secondary to BNMCT should be followed closely with detailed oral exams and dental radiographs to ensure that their pathology does not worsen over time.